Vanity Fair, August 1915

THE EXPULSION FROM EDEN

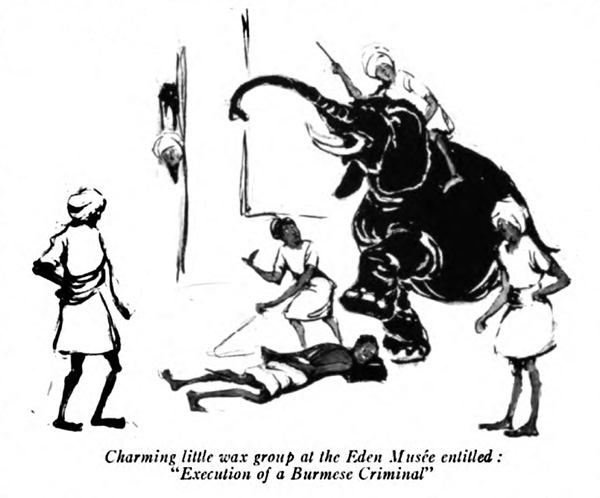

A Long and Sad Farewell to the Many Waxworks at the Eden Musée

By Pelham Grenville. Drawing by Thelma Cudlipp

AS I roamed through the cathedral-like stillness of the Eden Musée, the home of waxworks and horrors, which is soon to be closed forever to the public, it seemed to me that a chorus of ghostly “Wal, I swan’s” filled the air, as a million dead and gone visitors from Kankakee, Kalamazoo, and all points west, wandered past, leading hysterical infants by the hand and telling them that they had got to enjoy themselves even if they did have convulsions at the lovely horrors displayed to their view.

The exhibits at the Eden Musée are of all kinds, from the Czar of Russia to Mutt and Jeff; but all of them seem more or less steeped in blood. I don’t think I ever saw so much vital fluid collected in one place as there is in No. 38, “Beheading in Morocco,” though No. 35, “Execution of a Burmese Criminal,” is far from dry.

There are two absorbing problems opened by an inspection of the Eden Musée: why people think them attractive, and what are the essential qualifications which, in the eyes of the proprietors, render a person a fit candidate for the waxen Hall of Fame?

Of course, there are certain criminals,—Kaisers and other sensational murderers, who get in without question. But why, to name one instance, is Anna Held at the Eden Musée, and not Mrs. Vernon Castle? Why is E. H. Sothern given preference over Frank Tinney? Why is there no Jess Willard and no Billy Sunday?

There must be some system of admission and exclusion. Probably an admission committee sits, like the governing board of a fashionable club, and weighs the claims of all the applicants.

As to why people like to look at waxworks, that, I suppose, is answered by the fact that tastes differ. There are thousands and thousands of persons, for instance, who like to read the novels of Mr. Harold Bell Wright.

A more interesting subject for speculation is,—How does a wax-worked celebrity feel when he sees his image glaring at him with that expression of glassy imbecility which is so de rigueur in the world of wax?

Does William Jennings Bryan drop into the Eden Musée to correct a tendency to think too highly of himself after a more than successful tour on the Chautauqua Circuit? It would be hard to imagine a finer corrective for complacency. I seem to see these great ones breezing into the Musée, all pride and self-confidence, and creeping out into Twenty-third Street like punctured balloons. Even Donald Brian might doubt his physical charms if he saw himself in wax.

Whatever you may say in favor of the waxworks, they lack what you might call “action.” A public which can see its favorite movie-actor—for five cents, cash—shoot a dozen desperadoes, ride across country at a speed never less than a hundred and fifty-five miles an hour, and marry the girl at the end of the ride, will not spend twenty-five cents to stare at an immobile policeman holding up a motionless opium den. Get action! That is the slogan of to-day.

Yes, it is undoubtedly the movies which have killed the poor waxwork. The Eden Musée no longer has the power to draw the rustic from his native village. When the rustic wants intellectual refreshment, he takes it back home at the Hicks Corners Colonial or the Bodville Center Gaiety, and his children, spared the Chamber of Horrors, stand a sporting chance of growing to manhood with unimpaired intellects instead of becoming nervous wrecks at the tender age of seven through a too great acquaintance with the Eden Musée.

There is one group, however, which must give the directors of the Eden Musée a great deal of quiet satisfaction. I can imagine them creeping down into the chamber of horrors every now and then—when they are feeling a little depressed—to gaze at it, and smiling softly to themselves for a moment. It represents an untamed lion of the jungle and a film operator. A part of the film operator is inside the lion, the remainder—covered with blood—is waiting, with pained look on its face, till the motionless diner shall be ready for his next course.

FOR a moment, I say, the directors gaze on the group and smile. But their smiles die away, for film operators are so many, and untamed lions are so few.